DARK PLACES: Part I.

Go to church. Or the Devil will get you!

Dark Places

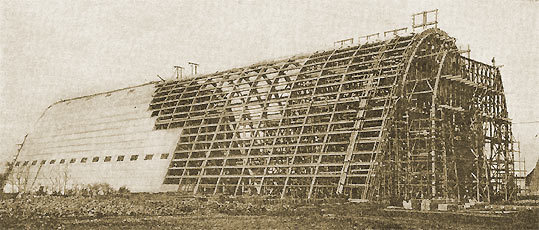

On the occasion of the Nord Fiction Festival on June 2022, the Ecausseville Airship Hangar (Normandy, France), a final remnant of an airship hangar of extravagant dimensions classified as a historical monument since 2003, was transformed into a creative lab. It played host to Dark Places: Part I. Go to Church. Or the Devil Will Get You!, the first episode of my on-going project titled Dark Places.

Press article: TRAX MAGAZINE - Comment l’artiste Cécile di Giovanni a fait construire une chapelle en plein festival ?

Dark Places focuses on depicting the functional and architectural metamorphosis of “charged places” and symbolic sites in the United States—places that hold personal significance for me.The project takes the form of a series of episodes, with each installment centering on a specific city, state, or region of America, as well as the stories and places crucial to my artistic research. For every chapter of Dark Places, I create a unique installation inspired by the selected story and location. The scale and scope of each installation depend on the exhibition space, allowing me to establish a dialogue between the space and the artwork.

In addition to the physical installations, Dark Places also includes a publication or documentation for each episode, resembling a detective’s diary. This diary reports various analyses and observations of the transformed elements and the creative process behind the resulting installation.

By focusing specifically on symbols, figures andplaces drawn from stories, events, and fictions that deeply impacted my childhood and adolescence, I seek to analyze and compare American material culture. I draw parallels between the changes they undergo over time with the evolution of the intimate relationship I have with them, and the symbolism they constitute for me and in the collective imaginary. Whether these symbols are at the service of fictions or are drawn from real events, how do their transformations and sometimes disappearance, impact the relationship that we have with the myths and stories to which these symbols are attached? What space do these symbols occupy, through their mutations, in our imagination?

The church and the hairship hangar

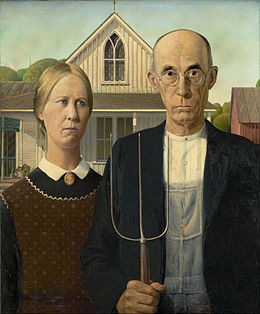

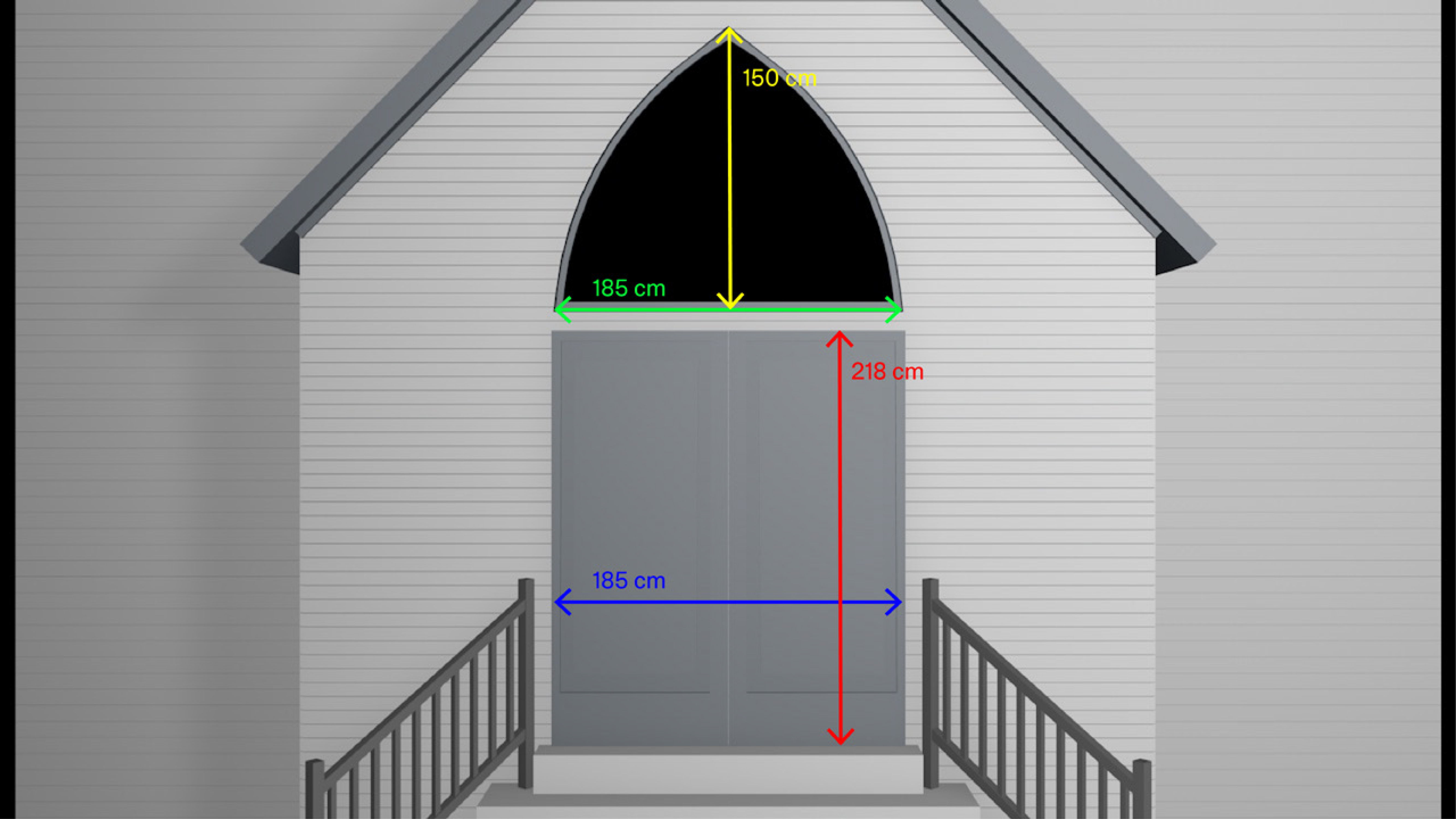

This first episode of Dark Places involved a collaboration with the collective Bankal & Decker. Together, we constructed a replica of an old, dilapidated American church. The church’s design drew direct inspiration from the Gothic style prevalent in the farms and chapels of the southern United States. Its appearance refers to the famous Grant Wood painting American Gothic, as well as other churches and farms featured in American pop culture through horror movies and music videos. Upon arriving in Normandy, I immediately recognized correspondences with isolated areas in the American South, such as Louisiana and Alabama, and drew inspiration for the installation from these links, embracing themes of the Southern Gothic genre.

The style of the church front, imbued with the aesthetic codes of the haunted house and horror fiction, is brought into direct confrontation with the austere surroundings and the history those surroundings embody. Constructed by the Marine Nationale, the French navy, during the First World War to hold airships used to combat German submarines. Later, the navy used the airship hangar to store artillery batteries until 1939. In June 1944, the Americans built workshops for their vehicles and weapons in the hangar, employing a number of prisoners there, hence the multilingual graffiti found there.

To dare to build a horror attraction in a place of war, almost draws us to envisage this old vestige of a history long passed as a theater imprisoned in its own story, a story that it continues to narrate.

“Go to church. Or the Devil will get you!”

The project’s title and its primary symbol, a red devil armed with a scythe, reference the story of a dedicated religious figure named W.S. Bill Newell. In the 1980s, he crafted and raised a sign bearing these symbols on his property, situated at the entrance of Pratville, Alabama. This sign, after vanishing in 2016 due to a storm, was reconstructed in 2018 by his sons, following requests from both motorists and local residents.

Merchandising

Limited edition of t-shirts on sale during the festival:

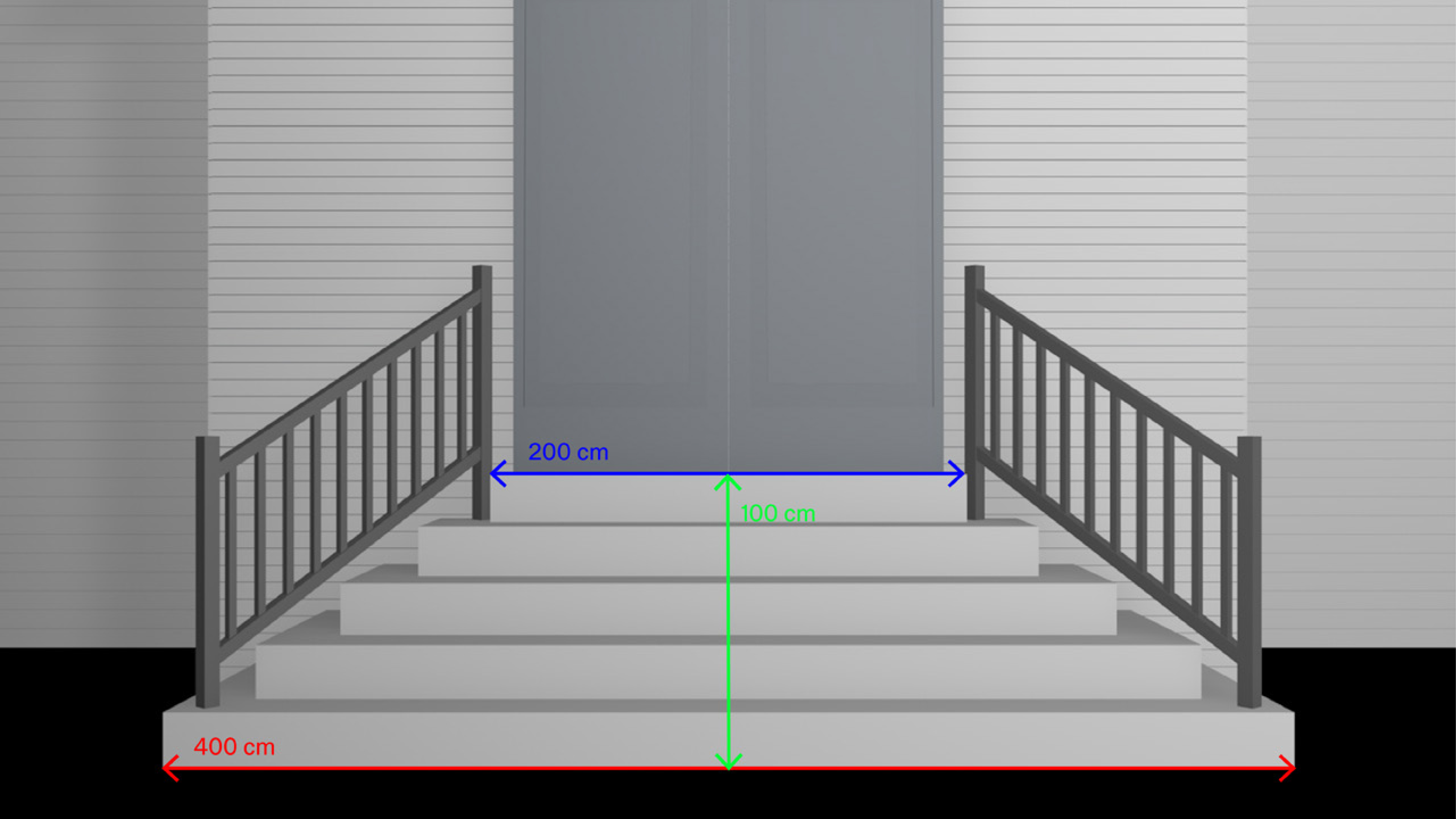

3D rendering of the church

Work-in-progress

Credits

Dark Places is an on-going project imagined and conceived by Cécile di Giovanni.

The installation was designed, built and conceived in collaboration with the Bankal & Decker collective (Nils Brunel, Arsène Filliatreau, Yoann Pellerin, Erwan Faucon-Lo Pinto) with the contribution of Theophile Varin, Lisa Slangen and Charles Cadic.

Photos: Romain Guédé, Arsène Filliatreau, Lou Nicolas, Louis Borel, Cécile di Giovanni.

3D rendering of the church: Sophie Mil.

Graphics and Dark Places visual: Lucas Masini.

Special thanks: Marlène Huard, Guillaume Toutain-Avy, the entire team of Nord Fiction festival, Paskal Lecureuil.